Source Control Best Practices

Why Source Control

If you want any number of reasons for using source control just Google it. This article is really just a regurgitation of so many others thoughts on the subject. But the truth is that through the years there have been very few clients for which I have worked, whether they have a team of one or 20 developers, that really understood the value of source control. For them I’ve written variations of what you are about to read.

![]() To this day I still meet the “developer” who lives and dies by the ‘ZIP’ file source control system. Really! Zip file are not source control. They are archives for historians to open up years from now to ponder what your code really did and how it came to exist. Instead, a source control system is a living, breathing entity that can tell you how your code got to where it is today.

To this day I still meet the “developer” who lives and dies by the ‘ZIP’ file source control system. Really! Zip file are not source control. They are archives for historians to open up years from now to ponder what your code really did and how it came to exist. Instead, a source control system is a living, breathing entity that can tell you how your code got to where it is today.

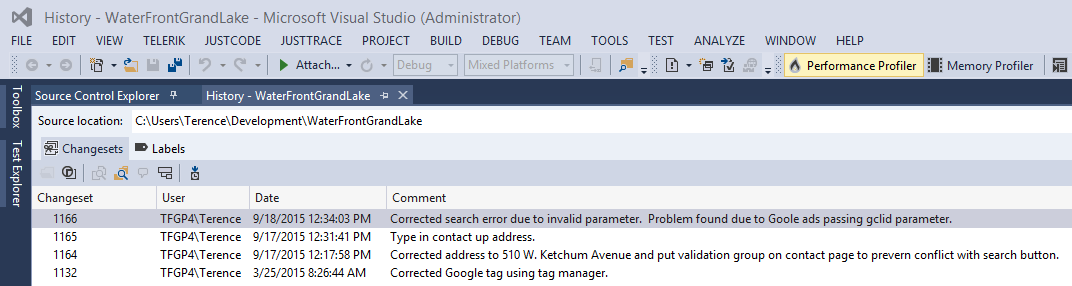

Now I’m not about to tell you what source control system to use. The few examples in this article are using TFS 2012 (TFVC), after all I am something of a Microsoft bigot (it pays the bills). TFS is really more than just a source control system and with the 2012 version Microsoft has even opened its mind to other possibilities for source control such as Git.

Check-In Code Often!

Source control provides developers the ability to keep a history of their changes. But, it only works if you check-in your code. So when you have something that compiles, check it in. The more often you check-in changes the less likely you’ll get into a situation where you have to deal with merge conflicts. The more often you check-in changes the least complex the changes will be. If the changes are not complex and you do run into a merge conflict, less work will be involved in resolving the conflict. Do your sanity (and the sanity of your team mates) a favor and check-in often.

This is the number one thing that I have to beat in to developers new to source control. “I’ll do it when I’m done”, “It takes too much time.”, “Why should I bother?” or “I forgot” are the classic excuses. Using source control is simply a habit you need to get in to! Its value only comes with time when an event such as an error requires you to roll back to a working version of the code.

Short story: I had a young programmer who could just not get it in to his head that he needed to check-in his projects. Over a three day period he worked on this project that excited him beyond belief. At least twice a day he would brag and show off the project to myself and another senior developer. We of course would ask if he had checked the new project in and his answer was “Yes, I will do that.” Well, you can only imagine the look on his face when on the third day he walked in to my office to tell me the project folder on his PC hard drive had corrupted. Of course my first response was just pull the latest copy from source control. The thing was he had continued to put off checking in his code and there was nothing in source control to fall back on. Needless to say he became a source control believer real fast after this.

Work on One Set of Related Changes at a Time and Keep those Changes Small

It’s more efficient to work on one thing at a time. Switching back and forth from task to task means wasting time getting into a different frame of mind and sometimes a different configuration. The more things you’re working on at once, the more likely that one set of changes becomes dependent on another and then you simply can’t check in your files until all the changes you’re working on are complete.

Think of this as the Single Responsibility Principle (stollen from SOLID) for source control. Isolating features in to discrete units of work allows you to easily rollback should you make a mistake or just start coding down a path that one hour later makes no sense. Small code changes help alleviate the merging nightmares that come with merging large chunks of code from multiple developers. Working on one function at a time eliminates the potential for multiple error in your code. Would you rather lose three days of work or just one hour? Do the math.

Write Meaningful Check-In Comments

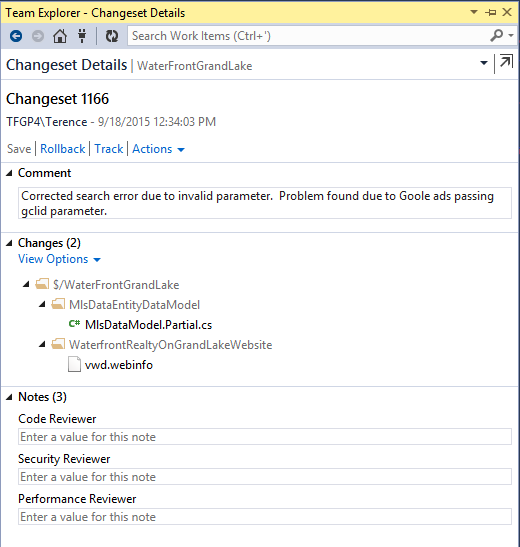

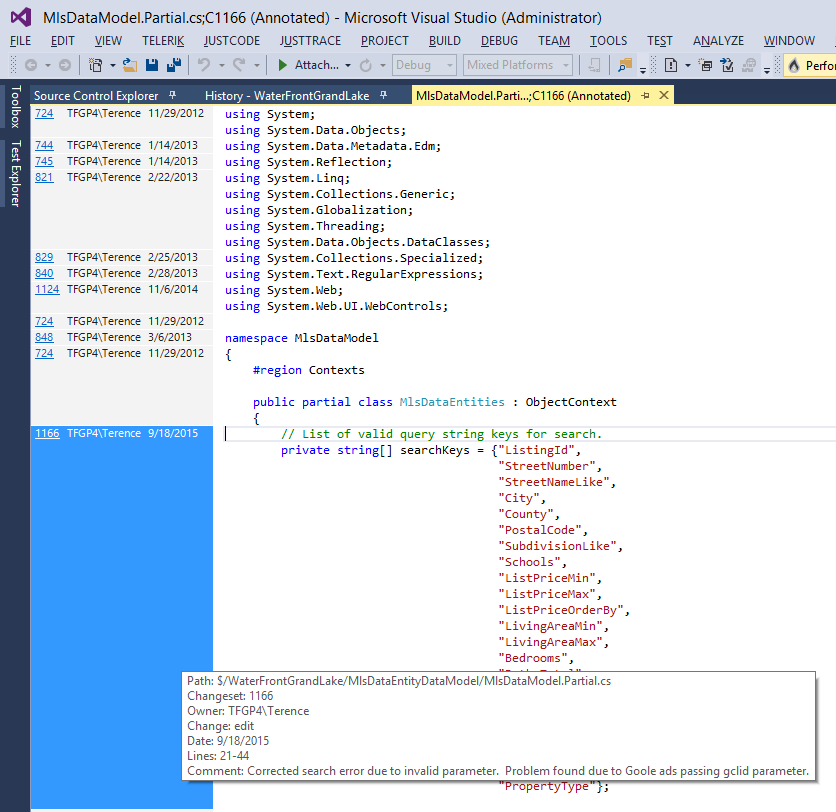

Without comments a source control system can only tell you what changed. It can’t tell you why you change what you changed. Be verbose and make your comments meaningful so that in the future you or others working the project can actually understand the history of the code.

The first thing I do on a TFS system is turn on the requirement for the comment field to have something in it before a check-in is allowed. Granted that not going to stop the developer from typing “Updated Code” or “Fixed Bug”.

Making meaningful comments requires a lot of practice and discipline. If you want to get good at it review you check-in history every week. Look at the comments together. Do they tell a story of what was developed that week?

Look at the files checked-in in each change set. Are each of those files pertinent to the comment and feature set?

Finally, look at the files. Does the annotation help you understand the code?

There’s an adage running around the internet that reads “Write every commit message like the next person who reads it is an axe-wielding maniac who knows where you live”. What it means is that if I am the axe-wielding maniac insanely trying to track down a bug in your code with comments like “My boss just made me check in today’s work”. Well, I’m coming after you!

Make sure Unit Tests Pass and the Code will Build before Checking-In

This means all unit tests. If you check in a change that causes a unit test to fail, someone else won’t know where to start to make that unit test pass. You’re wasting your time and setting the project schedule back by not ensuring unit tests pass before checking in changes. If your team allows it, use some sort of continuous integration suite. This allows you to get feedback upon every check-in that tells you whether all the unit tests pass. If you have a source control that supports it, enable guards that force the unit tests to pass before changes are allowed to be checked-in.

The same things stated above go for building a project. Do not check in code that will not build. If you check in a project with errors what good is it to another developer who needs to add a new feature? Do you really expect another developer to first debug you code? If you must check in code that will not build, don’t! Just shelve it for now. And if you find yourself shelving code often I would reevaluate your idea of what is a small unit of work.

Avoid Leaving Changes Overnight

Just like you would not leave a cake half done with the ingredients out over night for the bugs and your cat to get in to, you should not leave your code out overnight. If you have gotten in to good habits of breaking your work in to small functional units you should be able to schedule you day such that it is checked-in before you leave. If it’s not quite done, then comment the missing sections with TODO: and documents what remains in the check-in comment. So you’re only checking-in a subset of the work you wanted to complete. It’s still a unit of work, but remember it still has to build.

So why is this so important? Let’s just say overnight you won the lottery and have no intention of returning to the office the next day. Well, remember that axe-wielding maniac. Guess what? The boss just assigned him you project. Good luck enjoying all that money when he finds you.

Don’t put Generated Code in to Source Control

Source control provides the ability to roll back to a state in the past that allows compilation of the solution. Code that is generated as part of the build process can be generated at any time; there’s no need to put that code into source control. With lock-modify-unlock source control systems, generated code that is checked-in will be locked and cause errors during a build unless you unlock it on every build.

Still dependencies do need a home. So an exception to this rule is usually made with third party components for which you may or may not have the source code and the vendor has provided a compiled (versioned) dll. However, this is becoming easier as vendors are recognizing the need to easily integrate their product and as NuGet has become the standard for distributing code libraries. For example, in the case of Telerik, their install tools place DLLs outside the project \bin folder in a versioned library folder (\lib\RCAJAX\2015.2.729.45). NuGet does something similar by placing software packages in the packages folder defining a common practice for placing code DLLs in the \lib folder by version.

And don’t forget dependencies also include documentation. Any documentation that is related to the development and maintenance of your project should be in source control. When I pull a project down to my machine I expect it to have everything necessary for it to work on my PC. All the code, any supporting projects, DLL dependencies (vendors only), documentation on how to install it on a development, test or production system and of course the files necessary to build a working database.

In Summary

- Check-In Code Often!

- Bigger is NOT better. Small units of work are good.

- Don’t write a novel, but at that same time one word descriptors will not cut it so make your comments meaningful.

- If you can’t build it, you can’t check it in.

- Don’t leave your toys outside overnight. It’s no different than when your mother told you to put your toys away. So check in your code before you leave for the day.

- If you need it to build the project it should be in source control, but unless you don’t have the code or you have stood up your own internal NuGet server, compiled code should never be checked in.

I hope this has been of some help and as I said I’m not the only one to chime in on good source control practices. Just Google it.